The Government of Western Australia’s Department of Water and Environmental Regulation defines urban water as water that is used in populated environments.

It can refer to all water that occurs in the urban environment and includes natural surface water and groundwater, water provided for potable use, sewage and other 'waste' waters, stormwater, flood services, recycling of water (third pipe, stormwater harvesting, sewer mining, managed aquifer recharge, etc.), techniques to improve water use efficiency and reduce demands, water sensitive urban design techniques, living streams, environmental water and protection of natural wetlands, waterways and estuaries.

In recent years, the global increase in demand for urban water has led to many governments around the world introducing urban water management initiatives.

They aim to take into account the total water cycle to create cities and towns that are resilient, liveable, productive and sustainable in regard to their urban water usage.

In most urban cities around the world, the water that we use is collected from our toilets, sinks and washing machines and is treated for us to be able to use again.

Most conventional municipal urban water treatment plants follow a similar process, according to Springer Link:

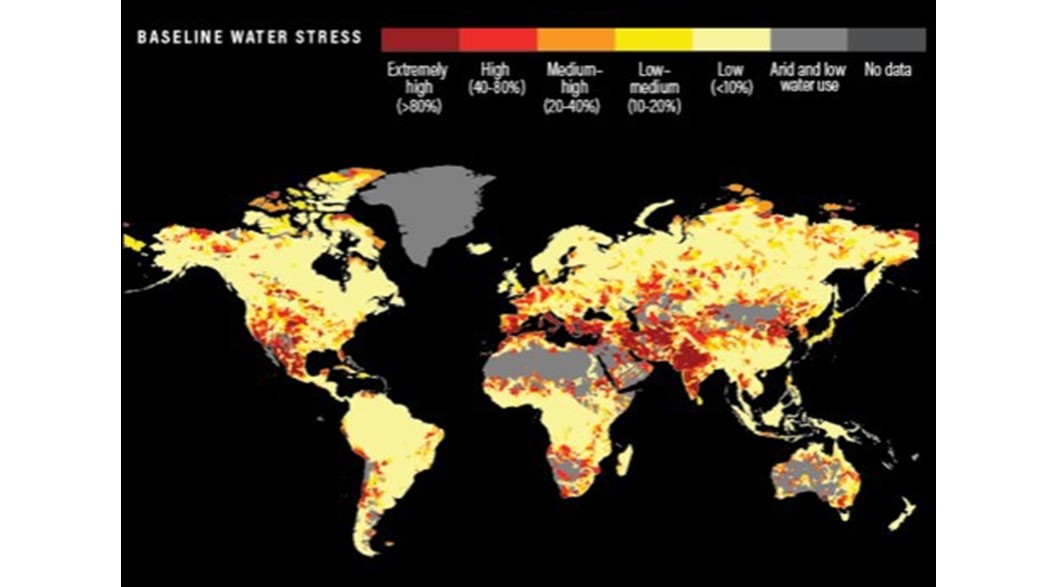

Bloomberg reported last year that 1.8 billion people in 17 countries are experiencing a water crisis. Of these 17 countries under high water stress, 12 are located in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA).

In terms of asking who is effected by water scarcity, India has the highest population of 1.4 billion people who are at risk. The issue in India is that their water crisis is not isolated to the southern states, Northern India is facing extreme ground water depletion.

Paul Reig, who leads the Aqueduct and World Resource Institute’s (WRI) corporate engagement on water told Bloomberg “[India has…] a very high dependence on groundwater to meet our demands, and because groundwater isn’t seen we manage it very poorly.”

As a region, MENA is extremely hot and dry. Current water supplies are minimal to begin with and the increased demand for water is adding to the already existing stress.

Climate change is also having an impact across MENA, The World Bank found that this region has the greatest expected economic losses from climate-related water scarcity, estimated at 6-14 per cent of GDP by 2050.

Where is water scarcity a problem?

The WRI recently revealed the top countries who have extremely high baseline water stress:

Australia is yet another country on the brink of a water crisis, according the National Geographic. A number of factors from a growing population to extreme droughts has set the country on a course for water scarcity.

Agriculture is the greatest drain on Australia’s water supply, using up nearly 70 per cent of the country’s water footprint. Meanwhile, 50 per cent of Australia’s agricultural profits come from irrigated farming, which is concentrated in the Murray-Darling Basin.

During the Millennium Drought, that spanned from 2000 to 2009, the government had to intervene due to extensive water over-extraction. As a result, severe water restrictions came in play that saw Australia’s cotton production reduced to 75 per cent, meat production cut in half, and rice farming coming to halt almost entirely.

At the moment, Australia has a sufficient amount of freshwater to meet its needs but the rising irregularity of its rainfall, climate change, and a growth of new urban cities and rural communities that need water systems are cause for concern.

This pressure on Australia’s water systems in predicted to grow as demand increases, coupled with the expected 10 to 25 per cent drop in river flow over the next ten years.

It can be difficult to pinpoint an exact time when water scarcity became a problem, as there are many factors that have led to the current water crisis.

Indeed, in some communities around the world water scarcity has always been present, but that could be due to lack of infrastructure, no access to a natural or clean fresh water source, or environmental barriers.

When we look at water scarcity to analyse why is has suddenly become a global crisis, there are three main factors that have played a role in its growth; pollution, agriculture and population growth.

Pollution

As a species we have to take responsibility for the damage we have caused to our planet and the pollution we have dumped into our water. From pesticides and fertilisers that we use in farming, to untreated human wastewater and industrial waste.

We have introduced harmful bacteria from our waste that can cross contaminate water and make it unsafe for us to reuse. Whereas our industrial progress has led to the devastation of environments that we are yet to see full extent of the damage.

Agriculture

Agriculture uses 70 per cent of the world’s accessible freshwater, according to World Economic Forum. Yet, 60 per cent of this is wasted due to leaky irrigation systems, inefficient application methods as well as the cultivation of crops that are too thirsty for the environment in which they are grown, WWF.

Due to this lack of efficiency, lakes, river and underground aquifers are dying out. Countries that produce large amounts of produce each year have reached, or are close to reaching their water resource limits.

Not to mention the freshwater pollution through fertilisers and pesticides, that can have serious health implications for both humans and animals.

Population growth

The United Nations estimated that in 1950 the human population was 2.6 billion, today that number has almost tripled to over seven billion people. This increase in population can be attributed to rapid economic and industrial development that has seen our water ecosystems transformed, at the cost of a massive loss of biodiversity, concluded to the WWF.

They also reported that 41 per cent of the world’s population live in river basins that are under extreme water stress. As a result, more people will also need more food, more homes and more water infrastructure to support these essential endeavours.

There are two types of water scarcity, according to Britannica: physical and economic.

Physical water scarcity is the result of a region’s demand outpacing the local water supply. It can be seasonal, with an estimated two-thirds of the world’s population living in areas subject to seasonal water scarcity. This is a proportion that is expected to grow as populations increase and as weather patterns become increasingly unpredictable.

Economic water scarcity is due to a lack of water infrastructure or poor water management. The FAO estimates that 1.6 billion people face economic water shortage.

In areas with economic water scarcity, there is sufficient water to meet human and environmental needs, but the access to it is limited. Mismanagement of drinking water treatment means that the accessible water is polluted or unsanitary. It can result from unregulated water use for both agriculture and industry.

There are many ways to help reduce water scarcity, including increasing agricultural efficiency, green and grey infrastructure investment and also wastewater reuse.

Increase agricultural efficiency

We have already seen the sheer amount of water that is wasted during agricultural procedures. Changes can include switching to seeds that require less water and improving irrigation systems that make use of precision watering, rather than conventional flooding.

Green and grey infrastructure investment

WRI and the World Bank’s research shows that grey infrastructure, such as pipes and treatment plants, and green infrastructure, wetlands and healthy watersheds, can work in together to tackle that issues of both water supply and water quality. Investment on new technology can massively improve the day-to-day water needs management for communities and businesses.

Wastewater reuse

It is time to take the plunge with wastewater reuse and start making effective use of this growing water management solution. Treating wastewater from plants, homes and industrial wastewater can effectively reduce our reliance and dependence on fresh water sources.

Leaders in treatment and reuse are already emerging, Oman are one of the most water stressed nations, treats 100 per cent of its collected wastewater and reuses 78 per cent of it. In the Gulf Cooperation Council countries, 84 per cent of wastewater is collected and is treated to safe levels, but only 44 per cent goes on to be reused.

Check out our essential guide to water reuse and discover how it can help reduce water scarcity, here.

It can be hard to truly access the effect water scarcity can have in the world today as already the effects are having terrible consequences on our wildlife, environment, health and society.

Global tensions increase

Freshwater resources are normally shared by more than two countries. If competition for fresh water continues it could lead to international conflicts over water. Treaties have outpaced disputes in the past 50 years, but the US director of national intelligence warned in a 2012 report that overuse of water could threaten the United States of America’s national security.

Reduced access to clean water

Without access to clean and freshwater we can become exposed to deadly water-borne illnesses and diseases. As the population grows, access to clean water is likely to decrease without united intervention. In third world countries where access to medical treatment is already limited, this could have serious implication for the people forced to drink this water.

Food shortages

Agriculture already accounts for about 70 per cent of global freshwater use to keep up with current food demand. We have already seen a need to develop new agriculture techniques to improve efficiency, but as the population continues to grow, the need for more food is inevitable.

Energy shortages

Energy production is one of the world’s greatest consumers of freshwater resources. Global electricity demand is projected to grow 70 per cent by the year 2035, reported the UN in 2014. One solution to the energy sector’s water demand is a switch to renewable sources that require less water.

Economic slowdown

The United Nations estimates that half of the world’s population will live in areas of high water stress by the year 2030. The economic ramifications when an economy is under water stress can be disastrous as the production of goods such as cars, food, and clothing are dependent on water.

It is clear that water scarcity is on the verge of becoming a global water crisis – if we continue to do nothing about it the consequence for every aspect of our lives will be affected.

We know the areas we need to address, and the technology is there for us to take the relevant steps to prevent water scarcity. Progress is being made daily from businesses adopting water reuse to developing better water management systems.

Now it is time for countries, businesses and communities to look at their water needs and usage, and take the action necessary to plan for the future.