Viewpoint: Out of REACH? EU programme declares war on PVDF membranes

Can the water industry survive without PVDF membranes? Should it be forced to lose its preferred material? Membrane expert Dr Graeme Pearce discusses the potential implications of the proposed extension of REACH regulations.

Membrane concerns

PFAS compounds are incredibly useful and woven through all aspects of products ‘essential’ for our daily lives. In the membrane industry, the most common material used is PVDF. This could itself be classed as a PFAS compound or is certainly made from PFAS monomers.

In recent years, PFAS restrictions have been greeted with enthusiasm in some quarters of the membrane industry, since they provide a new target contaminant and therefore a new opportunity.

However, others are worried that the membrane itself may fall foul of the restrictions. The initial concern was that membranes, particularly PVDF, may leach components or may breakdown thereby contributing to the problem of PFAS contamination of the environment. PFAS family tree

PFAS family tree

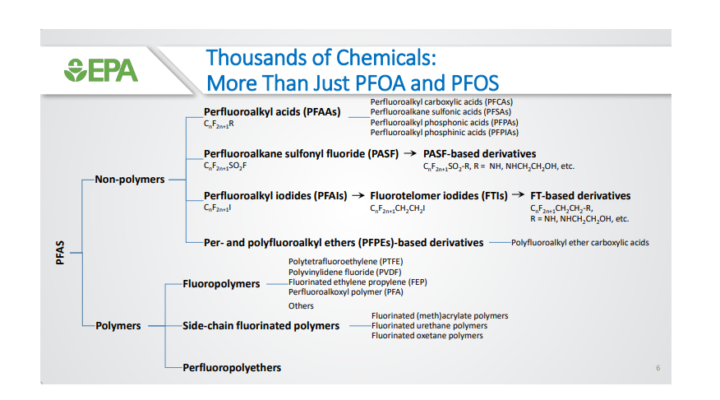

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has issued a family tree (above) describing the compounds included in the PFAS definition. Some commentators are more selective in their PFAS definition, but the tree shows that PFAS covers a broad range of compounds including polymers used for membranes.

While the EPA has focused on the effect of PFAS chemicals on health and the environment, the EU has decided to flex its muscles and try to tackle the cause of the problem. In 2006, the EU introduced REACH regulations, (Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals) which covered all aspects of the use of chemicals within EU member states.

“Does the threat from stable polymers such as the PVDF used in membranes justify such draconian control?”

At that time, these regulations posed a threat to membrane manufacture in Europe due to restriction or control of the use of aprotic solvents such as NMP. It took a decade before the regulation had teeth, but in the end, EU manufacturers were able to accommodate and comply with the solvent restrictions. The worst that could be said for membrane manufacturing in Europe is that new entrants faced greater barriers in setting up new facilities than in the past.

A case of over-reach?

Some fluorinated chemicals were also restricted under the original proposals and from a revision in 2017, but the effects were limited. However, there has now been a dramatic new development in the chemicals covered by REACH to include all PFAS compounds.

A proposed extension of REACH regulations is now out for consultation, and this is likely to have far-reaching consequences. The proposal would ban the manufacture and use of PFAS and if adopted in full, this would mark the beginning of the end for membranes such as PVDF made from fluorinated polymers.

“In the future membrane selection may not be determined by evolutionary pressures but by an administrator’s pen.”

Derogations may be granted for some PFAS chemicals in cases where there is deemed to be no alternative, but these derogations would be time limited. Of course, it is possible that there will be pushback which would allow PVDF membrane manufacture to continue under close scrutiny, but the direction of travel seems clear (see ECHA news).

In my view, it seems like a case of ‘Over-Reach’ - setting targets which are ‘Out of Reach’. Does the threat from stable polymers such as the PVDF used in membranes justify such draconian control?

Two thirds of the current membrane filtration market for water uses PVDF. There are alternatives but there are also reasons why PVDF is the market leader. I find it very concerning that in the future, membrane selection may not be determined by the normal evolutionary pressures of the marketplace but by an administrator’s pen.

A closer look at PVDF

Are PVDF membranes really that bad? Let’s have a quick look at the issues. The PVDF polymer is made from a fluorinated monomer. The resulting polymer is made into a membrane.

The membrane gradually degrades during its life in terms of its mechanical strength. According to leaching tests used for drinking water approval, it does not leach monomers or fragments injurious to health (except potentially as micro-plastics, but this is a different issue). At the end of its life, the membrane is disposed of through incineration or landfill.

“PVDF membranes are facing an existential threat.”

In terms of affecting the environment, there appears to be the potential for manufacturing risk, but this takes place in a series of controlled environments. In use, risk is negligible since the membranes are chemically stable. At the end of life, disposal is a more serious problem since recycling has always been limited due to fears of cross-contamination and disposal methods do impact the environment.

Constraints on these practices will increase due to new regulations. Perhaps the consequence for PVDF membranes is that manufacturing and disposal will be effectively off-shored, ie moved outside of the EU (and probably US), while ‘use’ may continue to be permitted, at least for a time. Eventually though, the use of PVDF membranes will probably cease entirely within the EU and other jurisdictions may well adopt similar restrictions.

PVDF membranes are clearly facing an existential threat and I fear that we could be in danger of throwing the baby out with the bath water. PES could be a short-term beneficiary, and it now seems highly likely that the recent trend towards ceramics will accelerate. There is no doubt that one way or another we are in for a decade of fundamental change for the membrane filtration industry.

I would be interested in the thoughts of others on this important issue – there is an opportunity to comment on the consultation here.

Dr Graeme K Pearce is a membrane technology specialist with 40 years’ experience in the membrane industry. He is the principal of Membrane Consultancy Associates.