With utilities seeking more ways to obtain recycled products from their sewage sludge, the production of biochar is one of the avenues that has seen the most traction. The product is a stable, solid form of carbon produced during certain advanced thermal sludge conversion methods, but mainly through pyrolysis.

A wealth of benefits

Adoption of these advanced thermal conversion technologies are being driven not only by their ability to recover useful products from sludge, but also by the concern surrounding micropollutants in sludge going to land.

This, and the ever-increasing volume of sludge produced, means that disposal routes are under the constant pressure of restriction, and diverting treatment plant waste into a useful product is looking to be an attractive option for utilities in the future.

Why produce biochar from sewage sludge?

Source: Gulthara; Shutterstock

Sewage sludge biochar (SSBC) production is a method of significantly reducing the volume of sludge a treatment plant needs to handle, and the solid product can boast properties that are amenable for many offtake markets. Although the high carbon content of many biochars makes them suitable to be combusted as fuel, producers are able to tweak their physical/chemical properties by altering feedstocks and production conditions, meaning biochars can offer value in many different ways.

These include use as soil amendments or for adsorption. For example, German company Pyreg markets its SSBC as a ‘P fertiliser’, or ‘phosphorus-charged biochar.’

“Not all biochar is created equally…When you make biochar from biosolids you have less carbon content and surface area [than that of woody materials], and it has a higher phosphorus content. This is advantageous for agriculture,” outlined chief sales officer Robert Kovach.

Pyreg claims that its produced biochar has a similar fertiliser efficacy as phosphate rock-derived triple superphosphate – which is currently widely used as an agricultural fertiliser.

Many SSBC producers also cite that their products have little to none of the micropollutants seen in the biosolids that are currently spread onto fields in many regions.

“People are more comfortable with other feedstocks, but we do have the science to show how much the pyrolysis process cleans up the sludge,” explained Wendy Lu Maxwell-Barton, executive director of the International Biochar Initiative, a membership-based organisation that includes biochar product makers, researchers, and government bodies.

Although some countries, such as Germany, prohibit the use of biochar derived from sewage sludge on fields due to concerns over its composition, others such as Denmark, the Czech Republic and Sweden are keen to use the upgraded product in agricultural settings.

“As the issues of PFAS and heavy metals in the sludge become more prominent, and countries stop allowing sewage sludge on fields, it’s bringing to the table what other solutions are out there. It’s a domino effect,” explained Kovach.

By using the product in alternative applications to combustion as a fuel, there is also a potential opportunity to sequester carbon instead of releasing it during burning. Research also suggests that the product is able to prevent the release of other greenhouse gases, such as nitrous oxide and methane, from the soil.

Tailoring the product

Sewage sludge is widely considered a cheaper feedstock than using straw or wood for the production of biochar, and it could prove to be a reliable and constant supply as sludge will always be produced at wastewater treatment plants. It is also common to use a blend of feedstocks in order to tailor the end-product properties, although the ratio of each input must generally be kept consistent in order to keep the biochar properties the same – something that may be important for customers in some offtake industries.

For example, Israeli company Earth Biochar is mixing composted municipal sludge alongside wood chips to produce its horticultural growing medium, which can be used to replace the peat-based composts that are increasingly being outlawed. The company chose this blend to utilise the structure contributed by the wood chips, as well as the mineral content of the sewage sludge, and the composting process allows for water removal from the sludge ahead of its transformation into biochar. The process now has approval from the Israeli EPA for the use of its end-product as a growing medium.

UK-based Standard Gas is offering a pyrolysis system that is feedstock-agnostic without recalibrating the process each time the input is changed. The company claims multiple feedstocks are a more economically viable option as it can add extra energy into the mix compared to using one feedstock alone. This helps power the system and produce excess for drying, as well as producing a very high calorie biochar.

“Utilities will have to find an alternative to land use [of digestate]. That could be paying to get rid of it, especially if it is outlawed… and the problem with incineration is the gate fee, which can be £85/tonne. There is also the issue of the high water content,” commented Standard Gas director Richard Jackson.

He also outlined that the company’s process is able to produce excess heat which can power the drying process – something that is not uncommon for advanced thermal conversion technologies. A key concern for utilities is the energy required for removing water from the sludge, before putting it through pyrolysis or similar.

Ironing out the obstacles

Although sewage sludge biochar is being touted as a way for utilities to access carbon credits – something that is hotting up across many industries as the drive towards net zero accelerates – some researchers are warning that there could be some caveats to its future in this space. The lower carbon content of SSBC in comparison to other feedstocks could negatively affect its competitiveness.

The nitrogen content of the sludge is also lost during advanced thermal conversion, which could be perceived as a negative by some buyers of the product, although this is less important outside of agricultural applications.

One key question mark is how long biochar (from any feedstock) is capable of storing the carbon for, particularly when mixed with soil – an environment where things are naturally breaking down. Those looking to offset their emissions using the carbon sequestration market are already gravitating to methods that store it for a significant amount of time – such as direct air carbon capture and storage – meaning that biochar could be out-competed.

However, the International Biochar Initiative pointed to the figures shown on carbon dioxide removal tracking site cdr.fyi, showing that around 80% of delivered carbon credits in 2022 were through biochar. This illustrates that the market currently has an appetite for the product, and that it could be a more immediately mature solution for those looking for sequestration.

Some proposed uses of the product do not double as a final disposal route, such as with adsorption – a process that separates components such as pollutants from wastewater by adhering those components to the surface of a solid. This would produce volumes of spent biochar that could potentially still end up in landfill. However, this offtake market is still attractive to utilities, because of its potential to be used on-site for treatment processes, and the increasing need for low-cost adsorbents.

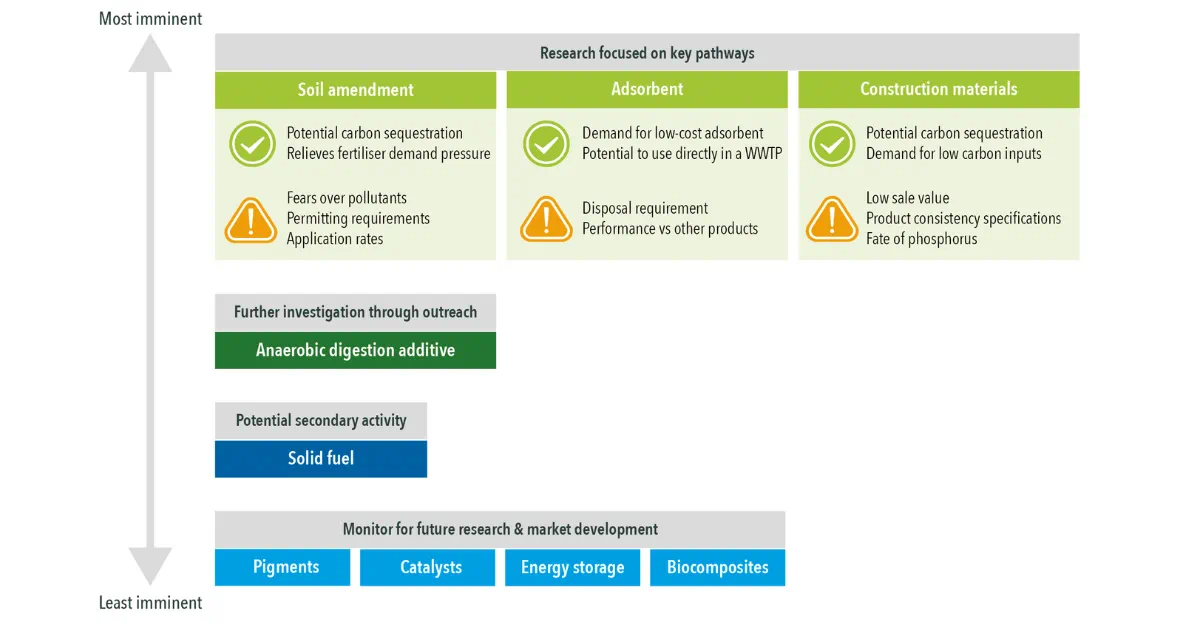

Source: Atkins; GWI

Key markets

A strong market for SSBC is currently in the US, where drying technology provider Bioforcetech has been achieving significant traction offering Pyreg’s pyrolysis system. The company has overcome the significant obstacle of drying the sludge by introducing its proprietary BioDryer to the market. The technology allows the sludge to reach the temperatures seen in the early stages of composting, in order to remove the water, using a lot less energy than regular thermal dryers. The company has been approved by the US EPA for the pyrolysis system it offers, now making it easier to implement successive installations in the US.

Elsewhere, biochar is being touted as a solution to problems in Europe, where space is limited and sludge is being banned for agricultural spreading applications. However, a major current obstacle for the product is its exclusion from the European Fertilizing Products Regulation, which aims to create a single market for recycled fertilisers and declare an end-of-waste status for better market uptake.

The European Biochar Industry Consortium – an association of biochar producers, wholesalers and refiners – is calling for sewage sludge biochar to be included in the regulation, citing improved visibility on how many advanced thermal conversion technologies can destroy micropollutants in the end-product. The fear of these pollutants currently contributes to SSBC’s exclusion from the regulation.

- This article has been produced by our knowledge partner, GWI, with thanks to the Atkins Bioresources Team for their contributions.